On Urban Nature

Sophia Hammerle

Last October, I watched a swarm of bees gather on the wall of an apartment building. They clustered around a small opening, flying in and out of a pipe roughly wider than my hand. Together, the bees formed a rumbling mass that clung to the honey-yellow stucco. I could hear their low, sonorous buzz from the ground where I stood. Watching, I was struck with both wonder and sadness. I knew they wouldn’t stay long.

“How do you experience nature in Los Angeles?” I asked in our call for submissions later that month. I was still thinking about the beehive. That evening, the sunset had turned the smog pink; light had bounced, golden, off the buildings downtown. I loved them, these bees, and the love wasn’t enough. Or was it? A mix of grief and resilience tinged this experience of urban nature. I couldn’t quite name it, but I could put a finger on the image, and I asked other writers and artists to do the same.

Our contributors responded with scenes of the urban landscape that are more than an imagined future: they are a cry for a liveable here and now.

These works will draw you out under the white, piercing light of a cloudless L.A. sky. They will urge you to “stand beneath that Sun and let it make you anxious,” as contributing author Maymoona Khan writes. These stories will compel you to confront complicity in the “grievous wounds” of urbanization, as Griffin Meehan describes the paving of the Los Angeles river.

Urban Nature grapples with the native and the nonnative, the manmade and the natural. J.G. Simiński finds the wilderness in human-built Lake Hollywood, where he is “hurled again into the godless.” John Recendez’s cry of “estábamos aquí primeros [we were here first]” comes up against invasive “radio towers and castor plants.” An unusually fat squirrel prompts Ellis Fertig to reflect: “I know this is something wrong, / not what nature had intended of us.”

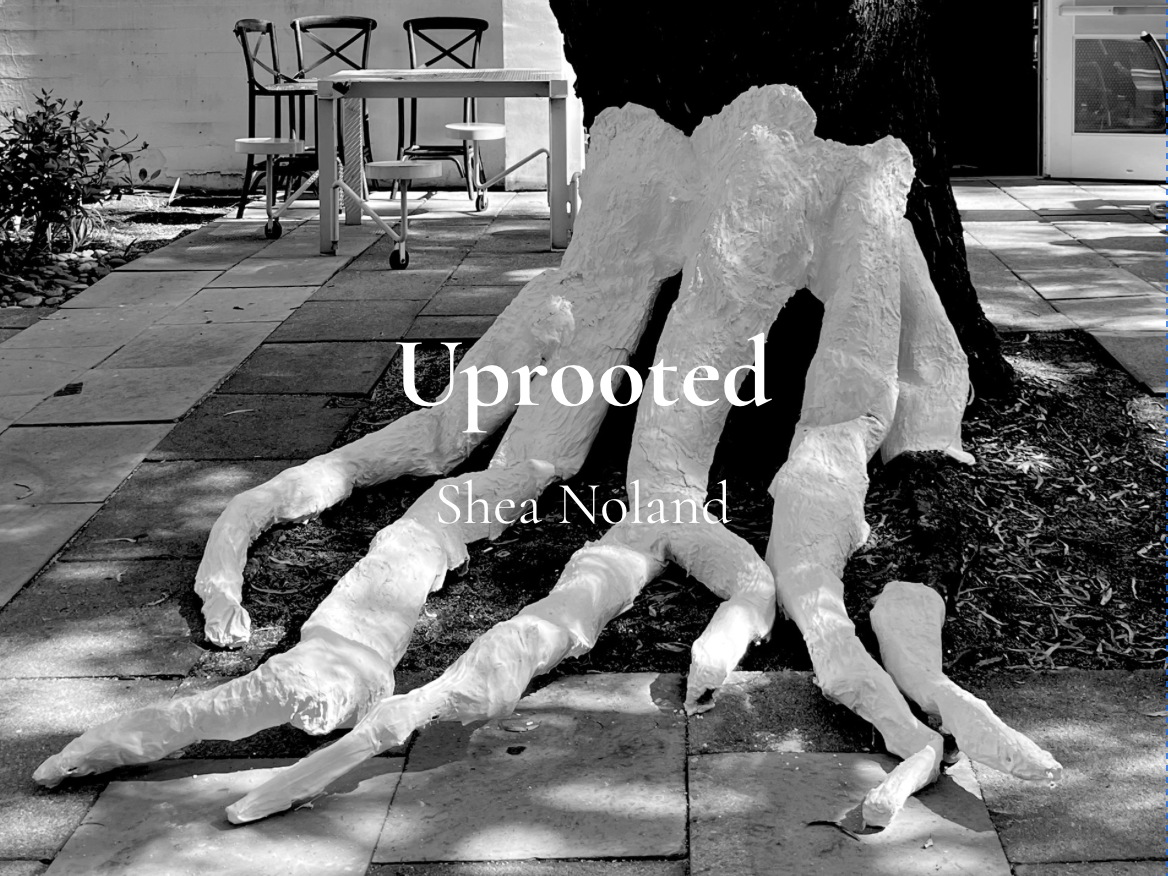

Readers will emerge from these pages with a new way of seeing Los Angeles. Our contributing photographers, artists, writers and sculptors make visible the nature that is hard to see in our city, often thought of as a concrete wasteland. Urban Nature emerges like tree roots erupting through pavement. Shea Noland’s sculpture “Uprooted” captures this wild resilience in the form of cast-like white roots furled from the trunk of a tree. Dorothy Steinicke reveals the mountain lion hiding around the corner in “A Walk in the Park.” Z.D. Dochterman imagines a post-disaster recovery of wildlife: steelhead trout in the L.A. river; toyon berries abundant.

Survival in the margins forms what Mark Reid terms “queer terrain” as he documents a queer urban landscape in Griffith Park. The oxymoron of Urban Nature demands a queer ecology, one that moves fluidly between the binary of wilderness and city, making a life in the spaces between. Sometimes, this existence is imagined before it is visible, as with Shristuti Srirapu’s “girls / who are almost as real as the wisps of ash that / chase the tops of palm trees.”

Urban Nature found another meaning after the January 2025 fires that devastated the Angeleno community. Our contributors put words to the unsayable. Poets responding in real time describe the disaster as both wild and human-caused, and they grieve accordingly. The rhythms of life in a capitalist system go on: at the supermarket, “the peas, still frozen, shame me,” Susan L. Lin writes. We watch the ash settle. L.A. becomes, still, again, “the city that glows,” writes Annika Harusadangkul.

Some pieces enact a form of remembering before loss: Marguerite Bysshe exhibited “Fire, Remembrance, Rebirth” months before the fires. Her solar prints on leaves tied to a branch enact a preemptive grief.

But there is still “time to run recklessly through wild forests,” as Ruby Seidner writes, urging us to care for the land from which we live. There is still time to see the wilderness in the city, to find the sublime in a concrete river or an unmowed lawn. As Brianne Donaldson writes, “Wildfire religion might be that passing moment when eyes are opened because tears are falling from them.”

—

When I returned to the site of the beehive three days after the first sighting, I saw only a strange dark stain. A few bees hovered in and out, but slower, and quieter.

A few weeks later, on USC campus, I paused in front of a silk oak. Native to Australia, the silk oak—like almost all of Los Angeles’ trees—grows here only because it was planted. Many nonnative trees depend on the alternation of the environment, getting water from the L.A. aqueduct and nutrients from synthetic fertilizers.

Still, the tree survives, like many of us planted here, making a life in the city. This silk oak towered over nearby buildings, and the trunk was too thick to wrap my arms around. I stood at the base of the tree, listening closely to a low, gentle buzzing. In the crook of its first two branches, about fifteen feet above where I stood, a hole in the trunk peered into a sliver of heartwood, a narrow opening roughly two feet tall.

The bees swarmed out.

—

On behalf of Reforestation Magazine’s editors and contributors, a direct donation was made to an Angeleno family who lost their home in the Eaton Fire. A second donation was made to support native coast live oak care and reforestation in impacted areas of Topanga State Park and the Santa Monica Mountains.

Sophia Hammerle is the founder and editor-in-chief of Reforestation Magazine. She studies narrative and gender at the University of Southern California, where she also leads monthly tree tours of campus. Her writing can be found in Orca, Eastern Iowa Review, and Dornsife Magazine, among others. When not writing or creating, Sophia is probably eating a mango, thinking about trees, or feeding a stray cat.